In the May teisho, I talked about using the sutras we chant during practice days such as this, and also carrying them with us as we walk the world. Today I’ll continue with focus on a few key perspectives that run through the sutras. I find it can deepen our consideration by looking at the same perspective expressed by different ancestors, as if we were looking at the same jewel through different facets. First – we are already Buddha; second – if so, why do we practice? And third – how do we practice? I had planned to address each in this talk, though I was too verbose to leave room for the third this round. I’ll touch on the third during the talks this coming sesshin.

I want to start with Torei Zenji’s Bodhisattva’s Vow. The first two lines are spoken by our chant leader alone:

I am only a simple disciple,

but I offer these respectful words:

The assembly continues with the rest:

When I regard the true nature of the many dharmas,

I find them all to be sacred forms of the Tathagata’s never-failing essence.

Each particle of matter, each moment,

is no other than the Tathagata’s inexpressible radiance.

Torei Zenji opens with a palpable humility. He is not claiming to be anyone special, only a simple disciple. And yet he follows by addressing us without hesitation or qualification. There is nothing but the Tathagata’s inexpressible radiance – there is nothing, nothing, nothing but Buddha. It is the combination of the humility and his willingness to speak clearly that stand out here.

Maybe there is a better way to describe this. Rather than humility, what we see in Torei Zenji’s introduction is an open mind. I could be totally deluded, but right now I have no doubt that each particle of matter is not different from the Tathagata’s inexpressible radiance. I am willing to state my perception as clearly as possible. Willingness to stand up and speak, while at the same time understanding that what I say may be mistaken, is a way to practice non-attachment to self.

I’ve seen other translations of Bodhisattva’s Vow that leave out these first two lines. What a shame it would be to miss them. Those two opening lines are one of my favorite parts of serving as chant leader.

Carrying Torei Zenji’s open-minded respectfulness, let’s continue to the first jewel – something fundamental running through our sutras, starting with the Bodhisattva’s Vow once again:

When I regard the true nature of the many dharmas,

I find them all to be sacred forms of the Tathagata’s never-failing essence.

Each particle of matter, each moment,

is no other than the Tathagata’s inexpressible radiance.

In “Song of Zazen, Hakuin says it this way:

All beings by nature are Buddha,

as ice by nature is water.

Apart from water there is no ice;

Apart from beings, no Buddha.

How sad that people ignore the near

and search for truth afar:

like someone in the midst of water

crying out in thirst;

like a child of a wealthy home

wandering among the poor…Truly, is anything missing now?

Nirvana is right here, before our eyes;

this very place is the Lotus Land;

this very body, the Buddha.

(Hakuin Zenji: Song of Zazen)

These words are so direct and strong it seems adorning them with any more words would just cloud rather than clarify. But here again, it is now Hakuin telling us that there is nowhere to go, nothing more we need find beyond what is already right here.

Would your practice be any different if you trusted these words? What if you did not need to fix anything with and through your practice? What if you and all particles are already inexpressibly radiant? If you could engage in your practice right now, without the burden of having to improve, or raise the bar for your achievements and behaviors, and without the burden of having to practice better, clearer, more diligently, would your practice be different? What if these lines from the sutras can be taken at face value?

this very place is the Lotus Land;

this very body, the Buddha.

We are not being given cause for grandiosity here, just reminders to see this body – your body – simply as it is, to see my practice – your practice – as it is, and the person on the cushion next to you as he or she is. No more, no less, and could not be otherwise. There is no original sin here, no need for desperation, just this. For that matter there is nothing special either.

Using this mind, we can each fully engage in Mu, this breath, with who hears, in this moment. This Mu does not have to redeem or resolve anything, just Muuuu…

Let me amplify a facet of this jewel from outside our sutra book. This from The Record of Lin-Chi:

Do you want to know who the Buddha is? S/he is no other than the one who is, at this moment, right in front of me, listening to my talk on the Dharma. You have no faith in her, and therefore you are in quest of someone else somewhere outside.

Ruth F. Sasaki, The Record of Lin-chi, p. 7

Rather than waiting for some additional experience, try to fully engage, with no external goal clouding the practice. Just this, now. And now.

This is the first jewel: we are already Buddha.

The second jewel in our sutras that I want to discuss is about why we practice. If we’re already home, there is a natural question that follows – then, why aren’t I done? Why get up so early in the morning to drive somewhere and sit?

In fact, Dogen asked that question repeatedly. In “Zazen Universally Recommended,” he wrote:

Fundamentally speaking, the basis of the Way is perfectly pervasive. How could it be contingent on practice and verification? The vehicle of the Ancestors is naturally unrestricted. Why should we expend sustained effort?

Of course he went on to say we should practice to “avoid repeated migrations through eons of time,” and tells us how. But let’s expand on the “why practice”.

Even as Torei Zenji speaks of each particle of matter, he offers enticement – how about now, can I see the inexpressible radiance in you, wall sconces, Zoom equipment, and everything I see and touch?

Many find their way to zazen out of suffering. I came to practice to save my life, caught in the labyrinth of my own mind. Even the ambition of finding solutions seemed self-involved, leading me to another blind passage in the labyrinth. The idea of improvement implied the need for improvement in order to be sufficient. Not recognizing this very body is the Buddha, and ambition to have that recognition – a dead end.

For this state, the ox herding series is too mild. It doesn’t capture the desperation of the mythic story of Boddhidharma’s successor Hui-k’o, cutting off his arm to demonstrate sincerity and commitment, so Bodhidharma would offer something that would resolve the turmoil of his mind. As the story goes, Hui-k’o – who was known as Shen-kuang before transmission from Bodhidharma- stood waiting for Bodhidharma’s teaching by standing steadfast as snow fell all night. In the morning Bodhidharma acknowledged Shen-kuang’s presence and asked what he wanted. Shen-kuang said:

“I beseech you Master, open the gate of the Dharma and save all beings.”

Bodhidharma said, The incomparable dharma can only be attained by constant striving…How can you…dare to aspire to true teaching…”

With this, it is said Shen-kuang drew a knife and cut off his hand….(Robert Aitken, The Gateless Barrier, p. 251)

I share this story reservedly; please don’t doubt your resolve, or yourself. Please use this story as encouragement to engage in this practice your way, and for your own reasons. There are cultural overlays such that what was encouragement in 5th century China is not the same as it is in the 21st century United States. In our culture too often we doubt ourselves in ways that undermine our engagement. You have your own reasons for attending this zenkai that do not require comparisons to anyone or anything. Honor your motivation as you would that of Shen-kuang, and the others with whom you sit today.

Taking this tale of Bodhidharma and Shen-kuang as an archetype, we can recognize the “why practice” question is answered not by a table of pros and cons. You can answer the question through recognition of that which brought your feet here today.

When all things fall apart, the call to practice is for wholeness. The “why practice?” question is answered by body and mind, beyond doubt, something has to be done. For me, Zen was not the first or only direction I looked for that something, but it was the one that offered a perspective that was outside the labyrinth of ideas, it required the use of mind in a different way.

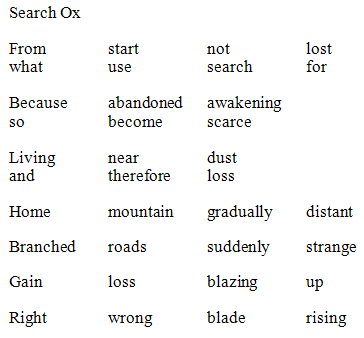

Writer and translator Lewis Hyde published translations of the poems accompanying the ox herding pictures that portray the Bodhisattva path. The portrayal changed over time, starting with five pictures, then eight, and what we have now is ten. The first picture is titled “Searching for the Ox.” Hyde provided several translations for each image, including a version with one English word to correspond to each Chinese character. This sparse version of the preface to the first ox herding picture goes like this:

Lewis Hyde, Max Gimblett, The Disappearing Ox; A Modern Version of a Classical Buddhist Tale, p. 14.

The first two lines address our question about why anyone would practice. From the start, not lost. What use is there to search? In the spare Chinese form there is no subject who is searching, and no object to search for. That is left entirely open, not defined by word. Then the second line circles the issue entirely; yet when we give scarce attention to that which is right here, we feel lost. The search is not necessary because nothing was lost, yet attention is called for when that very perspective is missing.

The next 6 words start us on our way: “Living near dust, and therefore loss.”

Suffering can be concrete or conceptual. It is grief of a lost love one, fear for our own life or the loss of the life we love. It is a change in fate such that our shelter and food are no longer certain, or the heartbreak of seeing others now without shelter and food. It is the loss of who we believe we are or should be, that can’t be distinguished from fearing our own death.

All this is well expressed in the first four lines of our early-morning chant, The Five Remembrances:

- I am of the nature to grow old.

There is no way to escape growing old. - I am of the nature to have ill health.

There is no way to escape having ill health. - I am of the nature to die.

There is no way to escape death. - All that is dear to me and everyone I love

are of the nature to change.

There is no way to escape being separated from them.

Our angst about this condition is in our DNA. I found some comfort in a story I heard from a client years ago. She had a dog with a neurologic disorder that resulted in his being unable to walk without leaning against something on his right side. She had the house arranged with cardboard that he could lean on to get around to important places. Once in a while he still fell over, lying on the floor twitching. I asked if the dog appeared to be suffering in those moments. “No,” she said, “He just looks at me with his tail wagging.” For a couple years I thought about that dog as my teacher. Without thoughts of comparison that he should be – life should be otherwise; he was content even lying there twitching. He was following the sutra telling us “The supreme way is not difficult if only you do not choose.” (Verse Of the Faith-Mind)

More recently it occurred to me that I was cherry-picking my data. I recalled that I have a personal animal story as well. There were times I was with my beloved family cat Frisky when he had seizures. He also lay twitching, but his were profound and persistent, and Frisky was unable to breathe during the event. Whether thinking or not, there was fear in his wide eyes that remained for hours after. He was traumatized and probably quite sore. But eventually the fear diminished, and Frisky relaxed like he was liquid, with no tension anywhere, as cats can do.

The experiences of this dog and this cat are not theirs alone. To see the experiences in animals we can also see how deeply these responses run in our animal bodies. We wouldn’t consider criticizing an animal for his or her reaction to a circumstance. Why should we doubt ourselves, whether in this moment we experience equanimity, or whether we experience terror?

Whether embodied or conceptual – it is all suffering of our animal bodies.

What can practice do to address this animal suffering? I could say nothing, and it would be true. But it would also not be the whole story. There is no changing the fact of death and loss, and to rely on equanimity as an answer is avoidance, not intimate engagement. Through our practice though, we also have access to experience as-it is, without embellishment or conceptualization, exaggeration, or dismissiveness. And so in the Heart Sutra we are told that Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva realized that in emptiness there is no suffering, cause of suffering, cessation, or path. Taking loss of a loved one as it is, the tears of loss are not separate from the love that drives it, or the flowers on the altar standing by.

To address the insult to sense of self, we can find a resource in Bodhisattva’s Vow:

All the more, we can be especially sympathetic

and affectionate with foolish people,

particularly with someone who becomes a sworn enemy

and persecutes us with abusive language.

That very abuse conveys the Buddha’s boundless loving-kindness.

It is a compassionate device to liberate us entirely

from the mean-spirited delusions we have built up

with our wrongful conduct from the beginningless past.

With our response to such abuse

we completely relinquish ourselves

and the most profound and pure faith arises.

How do we address the ubiquitous occurrences of insult to our sense of self? We relinquish ourselves completely. As one man I know expressed it, “this too is me.” This too is me experiencing equanimity in the face of critical illness as the dog. This too is me in pain and terror as the cat with a seizure. This too is me – feel free to insert your own story to which you cringe whenever it comes to mind…and it does come to mind, I’m sure.

There is no need to go out looking for suffering, it is inherent in life. It is enough to simply observe what is true for you. If our hearts are open and we care about those around us, is this different than attachment? And then how can we avoid grief and loss? Holding ourselves closed from engagement could be another form of aversion. Attachment, grief, and loss are not character flaws, or proof of deficient practice, they just join us with the whole of humanity, and beasts and birds. Our practice can address this, but we can all hit our limit in a given moment. Our practice at those times is to relinquish attachment to equanimity and just weep, whine, or otherwise join the full catastrophe. We can relinquish our aversion to aversion, and bring compassion to ourselves rather than blame. We need not resolve questions of self and no self; lean in to no separation and see if any questions remain to resolve.

The “Why practice” jewel in our sutras includes an additional component: our yearning for deepening experience of the Buddha way. I want to mention it, but I don’t know that I need say more about it. I expect that everyone here has a measure of it or you wouldn’t be here. Still, there are encouragements to our yearning left by our ancestors. Who can avoid a desire to join in when we read the beginning of the Heart Sutra?

Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, practicing deep Prajna Paramita,

clearly saw that all five skandhas are empty,

transforming all suffering and distress.

Encouragements like this give rise to faith that through practice something emerges within the experiences of suffering and distress.

Leaving the jewel of the way to practice for a future talk, I’ll end with a poem by Basho.

Your song caresses

the depth of loneliness,

O high mountain bird.Basho, trans. Sam Hamill, The Pocket Haiku, p. 38